‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’ Review: Henry Cavill and Alan Ritchson in Guy Ritchie’s Slapdash Tale of WWII Derring-Do

April 17, 2024

‘Nowhere Special’ Review: James Norton Brings Raw Feeling to Intimate Father-Son Drama

April 19, 2024The Palme d’Or winner is still hauntingly relevant as a portrait of surveillance, privacy, power and the dangers of action without reflection.

Two years after he leapt to the forefront of the New Hollywood with The Godfather, and just months before he picked up the threads of that operatic crime saga with the magnificent sequel/prequel The Godfather Part II, Francis Ford Coppola released a quiet movie, one in which sound itself — and, more specifically, its surreptitious recording — is the narrative engine. Arriving during a particularly fertile era for American film, The Conversation was not a hit, but it is one of the period’s most subtle and shattering features. Half a century later, it resounds as hauntingly as ever, not merely as a cautionary tale but as a searing portrait of where we are now.

If Coppola hasn’t maintained the box office muscle of his slightly younger contemporaries Spielberg and Scorsese, it’s in part because he’s gone out, sometimes way out, on moviemaking limbs. But he hasn’t always gone big; The Conversation is as restrained and unadorned as it is intricately crafted.

Coppola shifted that question from the visual to the aural: His central character, Harry Caul, is what another figure in the story calls “the best bugger on the West Coast,” though Harry prefers the more careerist terminology “surveillance and security technician.” In 1981, Brian De Palma would maintain the aural angle in Blow Out, his grittier spin on the Antonioni film, with John Travolta as a sound designer on crappy slasher movies who finds himself with a recording that he’s certain is proof of murder.

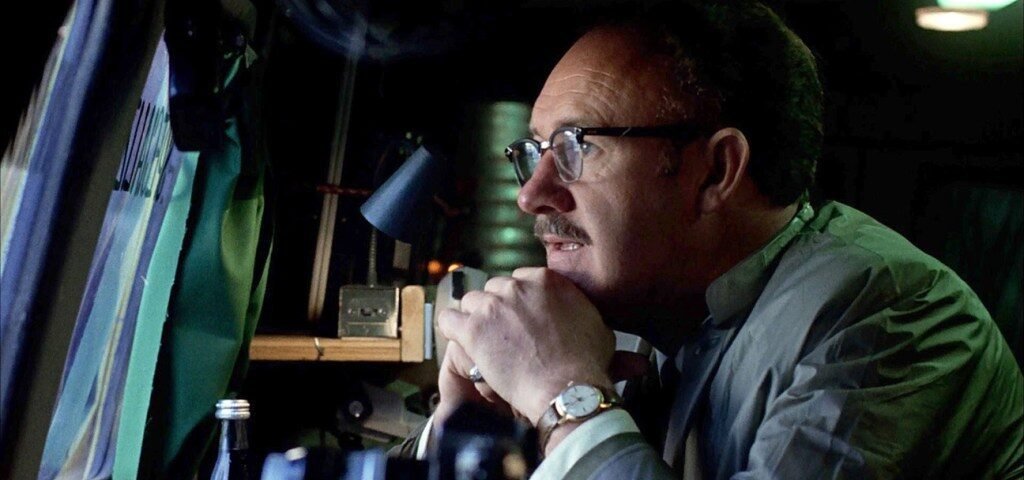

Occupying a realm between the trippy hothouse vibe of Blowup and the thriller machinations of De Palma, Coppola’s take is a sublime distillation. Its cast of ’70s luminaries includes John Cazale, Allen Garfield, Teri Garr, Harrison Ford and Robert Duvall, led by an exquisite, muffled gut punch of a performance from Gene Hackman as the tightly contained surveillance whiz.

Harry is in the midst of a particularly challenging assignment, recording a couple (Frederic Forrest and Cindy Williams, in a very different mode from the kooky cutie-pie she would soon become on Laverne & Shirley) as they move through the lunchtime hubbub of a public park, San Francisco’s Union Square. “I don’t care what they’re talking about,” Harry, struggling to separate their words from the midday noise, tells his sole employee (Cazale, in the second entry on his stellar, heartbreakingly short five-movie filmography). But Harry’s professed agnosticism toward his work begins to fray when his tapes suggest that the people he’s bugged are being targeted for murder by his client.

Perhaps the film character he has most in common with is Alain Delon’s hitman in Le Samouraï, a 1967 gem from Jean-Pierre Melville that was recently restored and rereleased. Stylistically, they’re worlds apart, one a figure of icy underworld glamour, the other what you might call an anti-hepcat. But they’re both loners who live in sparsely furnished monastic apartments and go elsewhere for sex. They’re mercenaries who pride themselves on their expertise. And their amoral devotion to unlawful work has brought each of them, unexpectedly, to a place of uncertainty.

Delon’s character uses a ring of keys to steal cars. The cops have one too, but they also have an ultra-sophisticated system involving, you guessed it, gallium arsenide transmitters. To us denizens of the digital age, the state-of-the-art eavesdropping technologies in these movies, with their dials and levers and reel-to-reel tapes, look quaint bordering on otherworldly. (But perhaps the most striking difference between then and now: In both The Conversation and Blow Out, public phones booths a) exist and b) are considered secure means of communication.)

At the time of its release, the resonance between The Conversation’s tech and the Watergate break-in was unmistakable but unintended; Coppola wrote the screenplay before the White House Plumbers’ malfeasance became front-page news. Party politics is not the point, anyway — then or now. Rather, it’s the chilling suggestion that when it comes to high-tech monitoring, we’re all vulnerable. As Neil Postman put it in his brilliant 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death, referring to George Orwell’s worldview: “It makes little difference if our wardens are inspired by right- or left-wing ideologies. The gates of the prison are equally impenetrable, surveillance equally rigorous, icon-worship equally pervasive.” Today, freelance snoops like Harry have given way to an increasingly centralized spy machinery, an unholy marriage of government and big business.